The lead motor finance commission cases, Johnson, Wrench and Hopcraft[1], were heard in the Supreme Court across three days from 1-3 April 2025.

The Court has indicated that judgment may be handed down in July, before the end of the summer term.

That judgment will have significant implications, not just for the waves of motor finance claims which are waiting in the wings, but potentially for intermediated credit models in other industries.

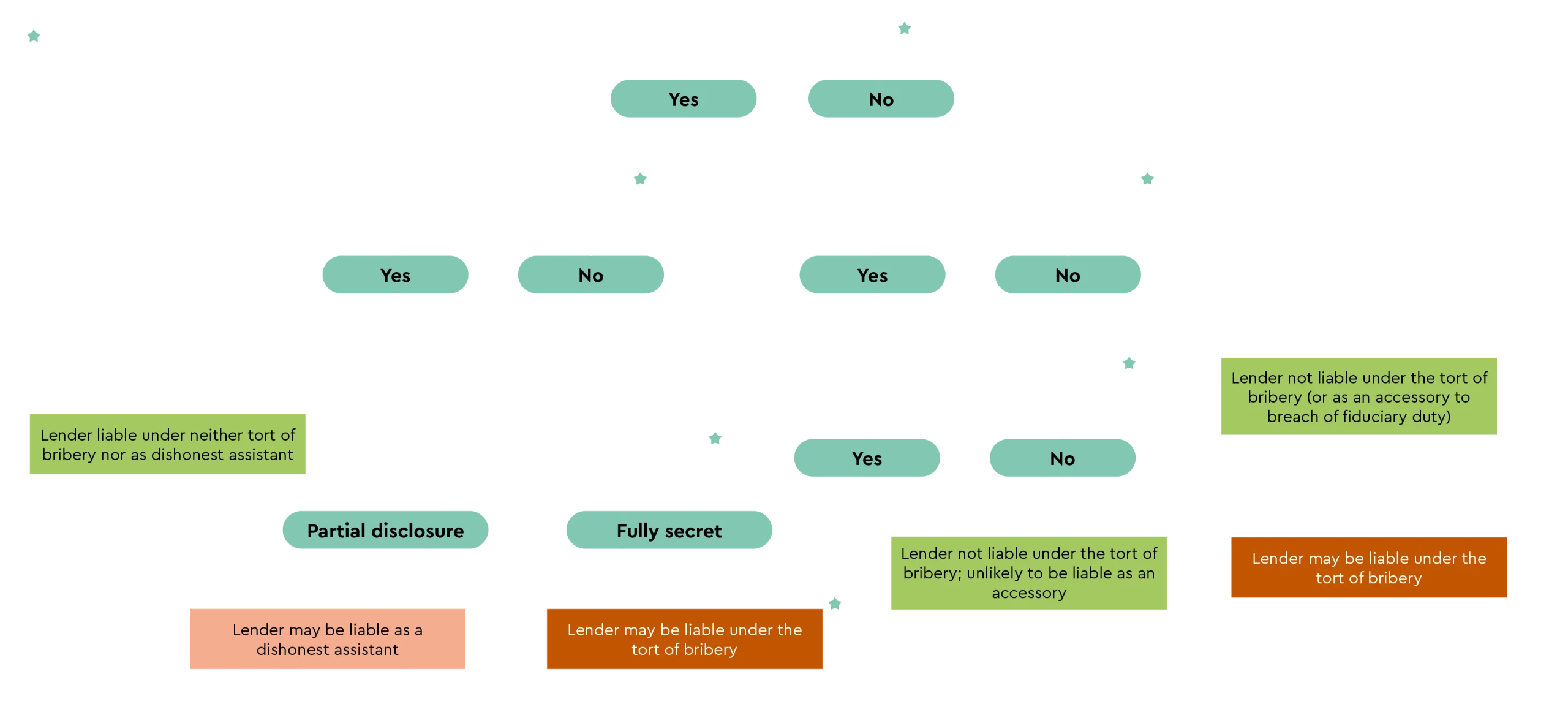

Understanding the potential for lender liability

NB. The Consumer Credit Act 1974 (CCA) poses an unrelated head of liability (where the proportion and type of the commission may be relevant). For example, in Johnson, the Court of Appeal held that the lending arrangement was “unfair” (for the purposes of s.140A CCA) to Mr Johnson because, inter alia, the commission paid by the lender to the broker was 25% of the total sum advanced, and because the sum borrowed and paid to the dealer was worth much more than the car was in fact worth.

FCA redress scheme? Any such scheme may further calibrate the factual tests to be applied to handle a high volume of consumer claims, in the interests of efficiency and commercial certainty.

A.

The background to the motor finance cases

The motor finance commission cases concern the commission paid to car dealerships by a lender for arranging the purchase of a vehicle on finance. Historically, this arrangement often involved a “discretionary commission arrangement” (DCA), where the car dealer (acting as broker) could negotiate the interest rate on behalf of the lender. The dealership earned a commission based on the negotiated rate, with higher interest rates resulting in higher commissions.

In January 2021, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) banned DCAs in the motor finance market. It also set out more prescriptive rules on the disclosure of commission arrangements in consumer finance products more generally.

Since then, there has been a wave of claims brought before the courts and the Financial Ombudsman Scheme (FOS)[2] by consumers who purchased their vehicles on finance prior to 2021. They argue that they have been overcharged on their interest rate and are entitled to compensation.

B.

Johnson, Wrench and Hopcraft

Three motor finance commission claims – Johnson, Wrench and Hopcraft – were initially brought (separately) in the County Court, and were heard together (as the lead motor finance cases) in the Court of Appeal in July 2024.

The Court of Appeal’s judgment was a landmark decision which has been of considerable interest: to participants in the motor finance markets; to the FCA, which is reviewing the need for a redress scheme for motor finance claims; and to participants in other markets who may be impacted by the Court’s findings.

Of particular note was the fact that, in each case, the dealer was found to owe (and to have breached) a fiduciary duty to the customer, by failing to obtain the fully informed consent of the customer to the payment of the commission. They were similarly found to have breached a so-called “disinterested” duty, to provide information to the customer on an impartial basis.

It was also significant that the lenders were found to be liable in each case, either as primary wrongdoers where the commission paid was completely secret (under the civil tort of bribery), or as accessories to the dealers’ breach of fiduciary duty where there was partial disclosure of the commission (so-called “half-secret commission” cases).

Finally, in Johnson, it was held that the relationship between customer and lender was unfair for the purposes of ss.140A-B of the Consumer Credit Act 1974 (CCA), with the effect that the Court was empowered under s.140B(1)(a) to require the lender to make a payment equivalent to the value of the commission.

C.

The issues for the Supreme Court

On appeal, the Supreme Court was considering five main issues:

- Do dealers, acting as credit brokers, owe consumers a fiduciary duty and/or a disinterested duty to provide information, advice or recommendation?

- Are the lenders liable in the tort of bribery (and does this require the existence of a fiduciary or merely a disinterested duty)? And if so, what is the correct approach to remedies?

- In half-secret commission cases, what level of disclosure is required to negate secrecy?

- If there was sufficient disclosure of the commission to negate secrecy, was there insufficient disclosure to procure the consumers’ fully informed consent to the payment such that the lenders are liable as accessories for procuring the credit brokers’ breach of duty?

- Is insufficient disclosure of commission enough to make the relationship between lender and consumer “unfair” for the purposes of ss.140A-B of the CCA?

We consider how the Court may approach some of these issues below.

D.

Are dealers fiduciaries? Rukhadze and the Supreme Court’s recent guidance

Between the handing down of the Court of Appeal judgment in Johnson, Wrench and Hopcraft and the Supreme Court hearing in April, an important (Supreme Court) decision was handed down regarding the duties and liabilities of fiduciaries. This was Rukhadze. [3]

Rukhadze offered some potentially helpful clarification as to the assumption of responsibility needed to trigger fiduciary duties. Per Lord Briggs, at [53]:

“It was then submitted that many modern commercial fiduciaries either do not know that they are in a fiduciary relationship or, if they do, fail to understand the duties which that entails. That may be so… The answer to perceived ignorance of these basic and relatively simple principles is better public legal education, and better education and training for those embarking upon a fiduciary undertaking, not a retreat by the law itself. Nor should it be difficult for someone who has undertaken a duty of single-minded loyalty to another person to understand that such loyalty is likely to be undermined by conflict of interest, or by making and keeping profits on the side”

Leading counsel for the lenders relied heavily on this paragraph, and in particular on the idea that there had to be an “undertaking” of a duty of “single-minded” loyalty. This seems difficult to square with a situation where:

- there is no active undertaking on the part of a dealer to act in the interests of a customer (even if such an undertaking can be implied); and

- the dealer informs the customer that they may receive a commission from the lender, such that their loyalty plainly does not sit entirely with the customer.

Of course, any analysis of whether a fiduciary relationship has been established will require careful analysis of the facts, and in particular of what was said and done by the dealer in any transaction. But the common-sense approach – and the one avowed by the FCA – may be that a motor finance dealer does not owe the sort of traditional fiduciary duty which would see it act in the customer’s interests to the exclusion of its own. And as the FCA observed in their submissions, the finding that motor finance dealers are fiduciaries would go beyond the standards established in the FCA Handbook, and have wide-ranging read-across to other regulated intermediaries.

This is of real importance in the case because, if the dealers are not fiduciaries, then lenders will not be liable in half-secret claims for dishonestly assisting a breach of fiduciary duty. It may also be relevant to secret commission claims, depending on where the Supreme Court ends up on the question of the disinterested duty – for which, see below.

E.

Are lenders liable in the tort of bribery?

There is a huge advantage to claimants if the lenders are found liable under the tort of bribery (which would be relevant in secret commission cases). They do not need to demonstrate that the bribe payer had a dishonest or corrupt motive. They do not need to show that the agent was influenced by the bribe. And as for remedies, it appears to be law that – where a party has paid a bribe – there is: i) an irrebuttable presumption that the bribe increased the cost of the relevant product; and ii) an entitlement to rescission as of right.

There was therefore significant discussion of the tort of bribery in the Supreme Court, with the lenders going so far as to suggest that the common law tort of bribery should be abolished altogether.

Whilst that may be unlikely (Lord Hodge, sitting on the panel in Johnson, having recently set out the requirements for bribery in another Supreme Court decision, Privinvest[4]), there remain some significant points to be clarified.

Foremost amongst them is the question of whether the tort of bribery requires that the agent (i.e. the individual to whom a bribe is paid) owes a fiduciary or a “disinterested” duty – and whether there is any difference between them.

The lenders submitted that the disinterested duty – which, in Wood[5], was sufficient for the secret commission to amount to a bribe – is essentially a common law analogue to the fiduciary duty. In other words, they are one and the same. This would have major ramifications. If the Supreme Court found that the fiduciary duty and the disinterested duty are identical, and they found that the dealers were not fiduciaries, then they would potentially deprive claimants of recourse against lenders.

The FCA argued that the fiduciary and disinterested duties are substantively different. It suggested that the disinterested duty is a lower threshold, which (inter alia) would prevent the dealer from taking secret payments from third parties (and which would thereby render any payers of a secret commission a briber). This would preserve the teeth of the tort of bribery, and fill what might otherwise be a gap existing where a secret payment is made by a third party to an agent not acting as a fiduciary.

It is difficult to know where the Court will land on this question. Practically speaking, the FCA’s approach has the merit of maintaining a potential avenue of recourse to customers where the secret payment is made to a non-fiduciary agent. But there are equally compelling reasons of legal principle for the view that the two duties are indeed synonymous.

As for remedies, it may well be that the Court chooses to revisit the irrebuttable presumption that the bribe increases the cost of the relevant product, as well as the automatic right of rescission where bribery has been found.

F.

What level of disclosure is needed to negate secrecy? And what about the customer’s fully informed consent in half-secret cases?

In Hopcraft, it was common ground that the commission was kept entirely secret from the claimant.

However, in both Wrench and Johnson, the lender’s standard terms and conditions referred to the payment of a commission to the dealers. And in Johnson, the dealer also provided the claimant with a suitability document, signed by Mr Johnson, which said that a commission may be paid.

The Court of Appeal’s analysis began with the principle that a commission payment is either secret or it is not. The question is therefore whether any disclosure was enough to negate secrecy. This is significant, because – pending the Supreme Court’s analysis of the tort of bribery, for which, see above – it will potentially dictate whether lenders are liable as primary wrongdoers or as accessories, with the important remedial implications which we have outlined.

The Court of Appeal found that, in Wrench, the disclosure was “buried in the small print of FirstRand’s standard terms“, such that secrecy was not negated, and the lender was thus found to be a primary wrongdoer in the tort of bribery.

By contrast, in Johnson, the first instance judge decided that the disclosure was sufficient to ensure that the commission was not secret (and this was conceded by Mr Johnson at the first appeal). However, the Court of Appeal found that the disclosure was insufficient to obtain the fully informed consent of the customer; this meant that the dealer was still in breach of their fiduciary duty (and the lender could therefore be held liable as an accessory).

The guidance which the Supreme Court will give on these issues will be gratefully received by market participants and the FCA. For their part, the FCA’s submissions as regards secrecy were that “in the ordinary case where terms and conditions disclose the possibility of commission being paid, that ought to be sufficient to negate secrecy for the purposes of the tort of bribery.” That appears to be a reasonable position. But this will inevitably be a fact-specific question. It will come down to the terms provided by dealers and lenders to their customers, and to the interactions with those customers. Any guidance given by the Court will have to navigate the Scylla and Charybdis of being detailed enough to be useful, but flexible enough to be responsive to particular transactions.

As for fully informed consent in half-secret cases – this is likely to remain a high bar for fiduciaries to reach. However, lenders will only be liable in those cases where they have been dishonest assistants; we discuss this further below.

G.

Dishonest assistance in half-secret cases

As we have separately briefed here, the Court of Appeal (applying Hurstanger[6]) had created some confusion when it came to the question of what constitutes dishonesty for the purposes of accessory liability on the part of the lender in half-secret cases. On one reading, the Court of Appeal’s judgment appeared to suggest that the state of mind of the lender was not relevant for the purposes of finding dishonesty, and that liability of a lender flowed automatically from the fact that there was no informed consent obtained from the customer.

This question was partly clarified by a recent Court of Appeal decision, in Expert Tooling.[7] In that case, the Court of Appeal reaffirmed the position that, for dishonesty, the requirements set down in Twinsectra remain applicable; that is, the lender must either have known about the broker’s breach of duty or deliberately turned a blind eye to it.

It seems unlikely that the lender in Johnson – a half-secret case – will be able to demonstrate that it has not been dishonest for the purpose of the Twinsectra test. The Court of Appeal had found, for example, that the lender’s engagement terms with the dealer in Johnson may in fact have discouraged the dealer from disclosing any commission to a customer.[8]

But other fact patterns may throw up different outcomes. During the Supreme Court hearing, Lord Briggs made the observation that it is difficult to think that ordinary, right-thinking people would consider a lender dishonest purely because they have paid a commission, without some other mischief. And the FCA, in their submissions, have emphasised the relevance of compliance with CONC disclosure requirements and the particular terms of the lender-broker relationship. For example, what if the lender’s terms specifically require that the dealer discloses the commission to the customer? In that situation, it seems hard to imagine that a lender would be considered a dishonest assistant. Again, this is likely to come down to a fact-specific analysis. But the Supreme Court may well give guidance which would give scope for lenders to demonstrate that they have not been dishonest (in the Twinsectra sense).

H.

Consumer Credit Act as release valve?

Of course, even if the Supreme Court finds against the customers on the issues above, the CCA represents a further potential means to compensate customers in secret and half-secret commission cases. This ground of appeal received little discussion at the Supreme Court hearing, but it is a live issue in Johnson, where the Court of Appeal had cited the size of the commission (25% of the sum advanced) and the fact that the sum borrowed and paid to the dealer was worth more than the car was in fact worth, as evidence of an unfair creditor/debtor relationship.

The drafting of ss.140A and 140B provides the Court with very wide discretion over the remedies available when they consider there to be an unfair relationship. As to the sorts of factors which may be relevant to the question of whether that relationship was unfair, it seems likely that the Court will consider things like the size of the commission, and its nature – for instance, whether or not it was a DCA, under which a dealer is plainly incentivised to push up interest rates – as material in deciding whether a customer is entitled to compensation under this ground. Any guidance laid down by the Court on these issues may have an important role in informing any consumer redress scheme.

I.

Watch this space

The Supreme Court has indicated that it may hand down judgment in July, at the end of the summer term. The FCA have separately said that they will confirm within six weeks of that judgment whether they are proposing a redress scheme, and if so, how they will take that forward. Any such scheme is surely likely to simplify the tests to be applied to handle a high volume of consumer claims, in the interests of efficiency and commercial certainty.

As the FCA footnoted in their submissions, in establishing a redress scheme, the FCA “is required to consider the relevant causes of action to consumers against firms under FCA Handbook rules, statute, at common law, or in equity.” The stakes for the Supreme Court could not be higher.

Footnotes

[1] Heard together in the Court of Appeal; Johnson v FirstRand Bank Limited, Wrench v FirstRand Bank Limited and Hopcraft v Close Brothers [2024] EWCA Civ 1106.

[2] On 9 May 2024, the FOS announced that it was dealing with around 20,000 open complaints related to car finance commission.

[3] Rukhadze v Recovery Partners GP Ltd [2025] UKSC 10.

[4] The Republic of Mozambique v Credit Suisse International & Ors [2023] UKSC 32.

[5] Wood v Commercial First Business Ltd & Ors [2021] EWCA Civ 471.

[6] Hurstanger v Wilson [2007] EWCA Civ 299; [2007] 1 WLR 2351.

[7] Expert Tooling and Automation Limited v Engie Power Limited [2025] EWCA Civ 292.

[8] See Johnson at [129]; the lender’s terms and conditions included the provision that “If requested to do so by the customer, you will inform the customer of the amount of any commission and or other benefits payable by us to you in relation to the prospective or actual regulated.”